California’s Housing Element

A Brief History

As the majority of Americans urbanized between 1910 and 1920, federal, state and local governments created new legal structures to plan for more orderly, healthful and safe growth. For example, given its rapid expansion from 60,000 to 3.4 million inhabitants between 1800 and 1900, New York outgrew its originally planned street grid several hundred years earlier than expected, and to address rampant crime, crowding, pollution and disease, the city established the country’s first comprehensive zoning scheme in 1916 (LA created partial zoning in 1908).

Assemblymember Pete Wilson’s 1967 AB 1952 added an income requirement to the general plan, providing a foundation for subsequent reforms to strengthen housing elements. As the stagflationary economy in the 1970s exacerbated affordability concerns, in 1971 the legislature authorized the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) to review local housing elements to ensure compliance to state guidelines, and in 1976, HCD added ‘fair share’ guidelines, which required regional planning commissions to determine housing needs segmented by income levels and then distribute these needs to its component cities. In the 80s and 90s, additional changes introduced incentives, such as density bonuses, to address a growing housing shortage which state planning efforts have to the present day been unable to address. Local exclusionary zoning and permitting is at least one contributing factor, though there is not a strong link between housing element compliance and actual housing production.

As these challenges affected cities across the country (Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle served both as socialist tract as well as scathing exposé of Chicago’s working class in the meatpacking district ), President Herbert Hoover established an advisory committee on zoning that produced a Standard State Zoning Enabling Act (SZEA) in 1924 that granted state legislative bodies the power to create zoning regulations and required each to create a zoning commission. In 1928, this model evolved into A Standard City Planning Enabling Act (SCPEA), which further empowered these commissions to create master plans for development, street planning, public improvements and regional planning commissions. In 1926, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of local zoning via Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co.

As these were advisory documents, not all states pursued their new powers to the fullest extent. Texas is the most prominent example, where cities may have zoning control within their boundaries, but counties and the state have very few legal structures to guide development more broadly, and Houston is [in]famous for having no zoning at all.

California’s 1929 Planning Act required counties to create planning commissions to construct a “comprehensive, long-term, general plan,” though only 27 counties complied by 1937, prompting a series of major amendments. These changes specified land use, conservation and transportation elements to be included in these plans, reflecting the state and county focus on soil conservation to preserve the agricultural industry. Although 1947’s Conservation and Planning Act attempted to reinforce the state’s central planning authority with a new Office of the Director of Planning and Research, political opposition eliminated the office within a year, and fragmented local systems were left without systematic coordination to respond to the hypergrowth that would begin following World War II.

In the decades following, California’s cities rapidly sprawled outward and created new problems of environmental degradation, smog pollution and traffic congestion. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, environmental and social activism had identified parochial zoning as a tool to enforce economic and racial segregation without sound environmental conservation practices. In response, the legislature in 1972 mandated comprehensive general plans and made local zoning subordinate to these plans. This was a major shift from advisory planning to state led, obligatory planning, which further specified that plans must include land use, traffic, housing, open space and public facility elements. In a series of other decisions in the 70s, the Supreme Court further codified local land use regulations and police power, which greatly diminished landowner and developer power and latitude.

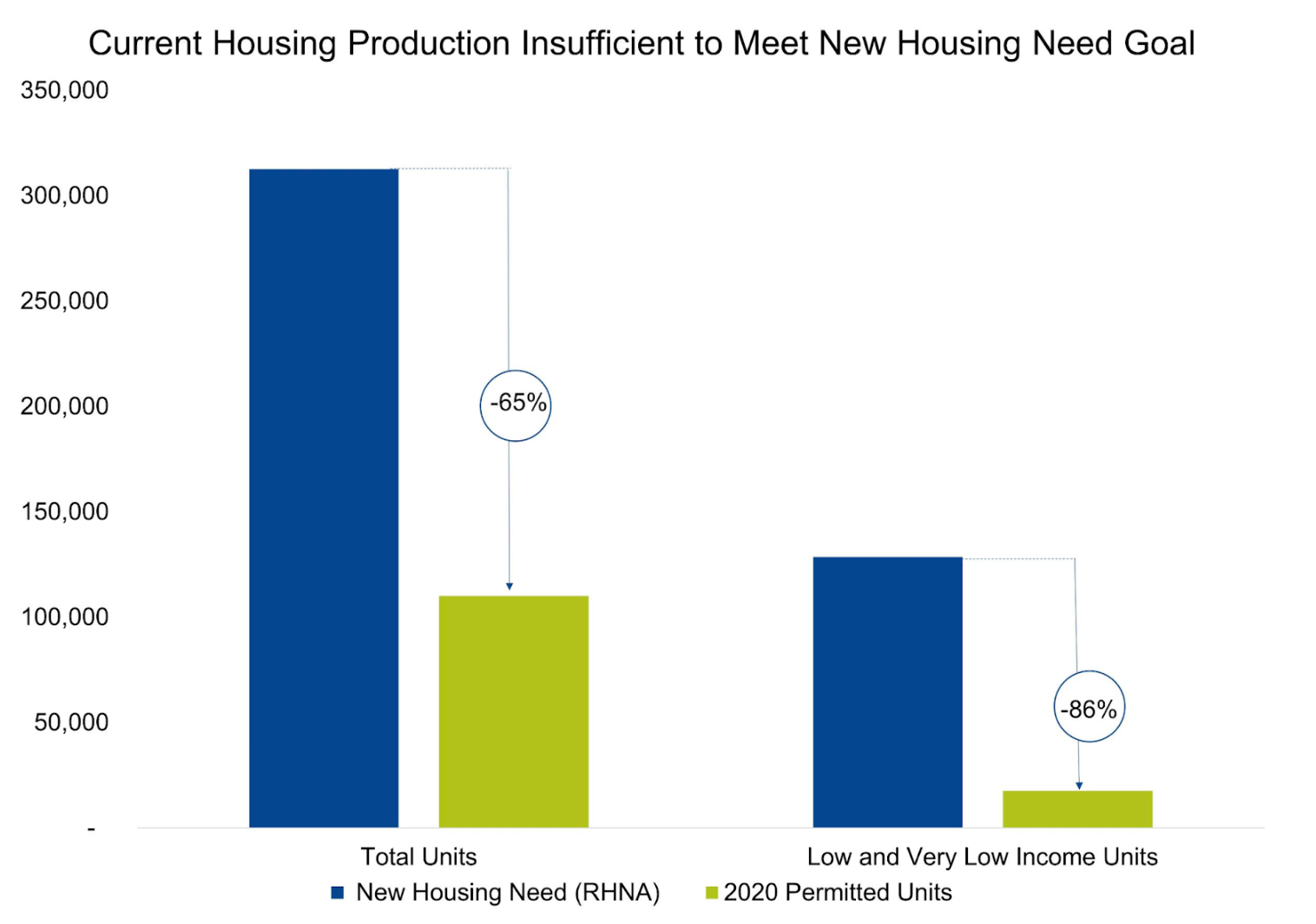

Presently, Government Code Title 7, Division 1, Chapter 3, Article 10.6 specifies how housing elements are to be developed and enforced and begins with a commitment to fostering intergovernmental cooperation to furnish housing to all economic levels in each community. Planning regions are split between 20 ‘Councils of Governments’ in metropolitan areas and 19 standalone rural counties. HCD creates a Housing Needs Assessment in consultation with either the COG every 8 years or with the county every 5-11 years, and those regional bodies then build a Regional Housing Need Allocation Plan (RHNA) to meet HCD’s need assessment (Here is the Bay Area Association of Governments’ RHNA, for example). The RHNA in turn informs how many units at each income level counties and cities must plan for in their general plans’ housing elements. However, the state continues to see underproduction, particularly for low income units, as housing elements remain planning documents with incentives, but no money nor requirements, to build.

Among a package of 150 housing bills in 2017, AB 72 (Santiago) granted HCD new powers to find a housing element out of compliance and to refer violations to the Attorney General, and SB 167 (Skinner) significantly amended 1982’s Housing Accountability Act to introduce the “builder’s remedy” which allows developments with sufficient affordable units to sue if it is denied building permits for a suitably zoned parcel. Attorney General Bonta established a Housing Strike Force within the DOJ in 2021 to expand the Executive Branch’s policing actions, including local zoning and permitting violations. The AG can sue for a court order to bring the housing element into compliance, and 12 months after such an order, if the jurisdiction remains out of compliance, the court can impose a $10,000 - $100,000 per month fine to be paid into the Building Homes and Jobs Trust Fund. 3 months later, the fines can be trebled, and 6 months later, by a factor of 6, at which point the court can also appoint an agent to bring the housing element into compliance.

A March 2022 State Audit concluded that HCD’s Housing Needs Assessment used a flawed methodology that artificially lowered its projections in some instances, did not validate staff data entry properly and could not demonstrate considerations for all factors defined by state law. A May 2019 UCLA Policy Brief argued that HCD’s assessment numbers are politically motivated and overly complicated and suggested that instead of projected housing needs based on population growth and segmented by income, all cities should be required to maintain a fixed percentage of income restricted housing, something that has been successful in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and France. Over the long term, the authors posit that a demand based system could link growth planning to higher rents and costs. In August 2021, the Terner Center published a case study on Los Angeles’ data-driven approach to creating its housing element, where planners incorporated statistical probabilities of parcel development.

1. The Tenacity of Parochialism: State Planning, 1929-1959. California Legal History Journal, Volume 13: 2018. Chapter 5, pg 213. https://www.cschs.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Legal-Hist-v.-13-2018.pdf↩

2. 150 Years of Land Use: A Brief History of Land Use Regulation. James Longtin. 1999. https://www.cacities.org/UploadedFiles/LeagueInternet/91/91ed1e31-0a7b-43cf-b7c4-260ad9de2e0f.pdf ↩

3. California’s Housing Element Law: The Issue of Local Noncompliance. Paul G. Lewis. 2003. Public Policy Institute of California. https://www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/content/pubs/report/R_203PLR.pdf ↩

4. 2022 Statewide Housing Plan. CA Department of Housing and Community Development. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/94729ab1648d43b1811c1698a748c136 ↩